Adapted and updated from Paul Kivel, Uprooting Racism: How White People Can Work for Racial Justice

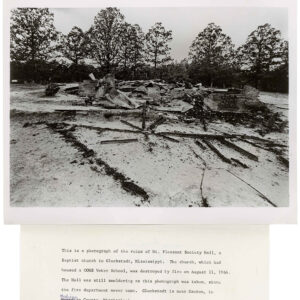

(Ruins of the Mt. Pleasant Society Hall in Gluckstadt, Mississippi–where an African American voting school was being hosted, August 11, 1964. Photo from the Library of Congress.)

Many of us have come to take our right to vote for granted, forgetting our foreparents’ long struggles to achieve it. People fought for hundreds of years to extend the right to vote beyond the rich, white, property-owning Christian men who created the very national and state voting laws that excluded everyone else. Beginning in 1790, states gradually moved from relying on property qualifications to those based on gender and race. By 1856, all white men could vote regardless of property— but nobody else could. With the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment1 in 1870, African American men gained the right to vote. In 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment2 gave white women the franchise. The 1965 Voting Rights Act3 gave women of color the right to vote and eliminated poll taxes, literacy requirements and other impediments to voting. However, that is not the end of the story because for millions of people in the US, particularly people of color, voting is still not possible or remains incredibly difficult. Our voting system—and therefore our Democracy—is corrupt and broken.

In this time of multiple crises, we face a crucial presidential election in which we must choose someone who can guide us through a pandemic, a climate emergency, a possible economic crash and many other serious challenges. Many people in the US are placing their hopes on who we get to vote for (the primaries and national conventions) and who gets elected in November. Even though the 2000 election was corrupt and the Republican party, with the help of the Supreme Court, staged a coup to give the election to Bush, and even though the 2016 election was corrupt and the Electoral College threw the election to Trump, even though he lost the popular vote by millions, many people still assume the system is essentially fair and democratic because it is based on the principle of one person, one vote.

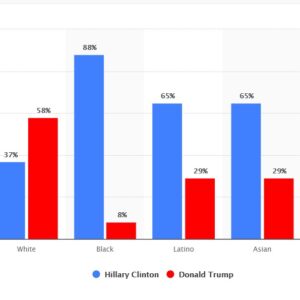

Preliminary data for the 2016 presidential election in the United States show whites constituted 79% of Donald Trump’s total vote, while 79% of the people of color who voted, voted for Hillary Clinton. But were people of color adequately represented? Did all of their votes count? 4 African Americans and Latinx in this country (71 million people or about 30% of the population ) are grossly underrepresented and it takes organizing, not voting to fix that.5

(2016 votes by race. From Statista)

Denying people of color the right to vote is a practice deeply embedded in the US political system and we need to understand that history so we don’t consider the present practices anomalous. Our Founding Fathers, in a compromise to ensure Southern states would participate in the union, agreed that slaves, although they could not vote, would count as 3/5 of a person for the purpose of calculating the number of Electoral College representatives allotted to each state. The number of representatives was, in turn, used to calculate the number of electoral votes each state would have. This compromise gave the Southern states a political advantage so powerful the US had southern slave-owning presidents for 50 of the first 72 years of the country’s history.6 (For full refresher on how the Electoral College works, see this brief explainer.)

Even today the two-party, winner-take-all Electoral College system continues to discriminate against and marginalize people of color. In the 2000 election, Bush won the electoral votes of every Southern state and every border state except Maryland, despite the fact that 53% of all blacks (over 90% of whom voted for the Democrats) live in the Southern states. There are more white Republicans than black voters in each of those states, so the Electoral College discounted the votes of over 1/2 the people of color in the country. Millions of Native American and Latinx voters who live in overwhelmingly white, Republican states like Arizona, Nevada, Oklahoma, Utah, Montana and Texas have been equally unrepresented by Electoral College voting.

A further dilution of the votes of people of color occurs because of the way electoral votes are unequally distributed between rural and urban states. For example, in Wyoming in 2016, one Electoral College vote corresponded to 195,000 voters, while in California, with more voters of color, the ratio was one Electoral College vote to over 711,000 voters. Another way to understand this impact is that nationally, African American votes weigh 95% as much as white votes, Latinx votes are on average 91%, and Asian American votes 93% as much as a white vote.7

Representation in the US Senate is similarly skewed. Vermont’s 625,000 residents have two United States senators, and so do New York’s 19 million. Just across the state line, a Vermonter has 30 times the Senate voting power that a New Yorker does. The nation’s largest gap, between Wyoming and California, is more than double that. In fact, the 38 million people who live in the nation’s 22 least populated states (including Wyoming) are represented by 44 senators. The 38 million residents of California are represented by two senators. The US Senate may be the least democratic legislative chamber in any overdeveloped nation in the world.8 This gap in representation is widening and has major racial implications. By 2025, the four states of New York, California, Texas and Florida will have non-white majorities and 25% of the nation’s population but will have the same Senate representation as the four states of Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, and North Dakota.9

The Electoral College system is not the only way people of color lose voting representation. After emancipation and the passage of the 14th and 15th amendments, the Southern states worked to exclude newly enfranchised black voters. The white ruling class of the South was very explicit about what it was doing. For example, in Virginia, US Senator Carter Glass worked to expand disenfranchisement laws along with poll taxes and literacy tests. He described the state’s 1901 convention this way:

Discrimination! Why that is precisely what we propose. That, exactly, is what this Convention was elected for — to discriminate to the very extremity of permissible action under the limits of the Federal Constitution, with a view to the elimination of every Negro voter who can be gotten rid of legally, without materially impairing the numerical strength of the white electorate.10

In Alabama, the criminal code in the state constitution of 1901 was, according to the chair of the convention John Knox, designed to “ensure white supremacy,” and crimes worthy of disenfranchisement were classified depending in large part by whether delegates thought blacks were likely to commit them.11 The state was also focused on excluding poor whites. Delegates “wished to disfranchise most of the Negroes and the uneducated and propertyless whites in order to legally create a conservative electorate,” wrote historian Malcolm McMillan.12

Creative Commons

Historically, another way white people disenfranchised voters of color was by disenfranchising felons — but not just any felons.13 Many states disenfranchised criminals even before the Civil War. But after the Civil War and Reconstruction in the South, legal codes were created to limit the effects of the 14th and 15th amendments that gave blacks equal protection under the law and gave black men the right to vote. In Mississippi, the convention of 1890 replaced laws disenfranchising all convicts with laws disenfranchising only people convicted of the crimes blacks were supposedly more likely to commit.14 For almost a century thereafter, you couldn’t lose your right to vote in Mississippi if you committed murder or rape, but you could if you married someone of another race-a law particularly aimed at (and enforced primarily against) Black men who married white women. In Florida, the constitution drafted in 1868 disenfranchised ex-felons as well as anyone convicted of larceny, a crime whites believed ex-slaves were most likely to commit.15

The provisions implemented during those post-Reconstruction conventions, from poll taxes to grandfather clauses16 to literacy tests, were almost all struck down by the Civil Rights Act of 1965. The only ones still standing are felony provisions, which leave 5.17 million people, including 2.2 million black men (approximately 1 out of 16 African Americans total) currently denied the right to vote because of incarceration or past felony convictions.17 In Florida, Kentucky, and Virginia more than 1 in 5 African Americans can’t vote for these reasons.18

As journalist Nicholas Thompson of the Washington Monthly noted, “Three out of every five felony convictions don’t lead to jail time, and there’s no clear line you have to cross to earn one…. Stopping payment on a check of more than $150 with intent to defraud makes you a felon in Florida. Being caught with one-fifth of an ounce of crack earns you a federal felony, but being caught with one-fifth of an ounce of cocaine only earns a misdemeanor.”

Besides being arbitrary, racially biased and a continuation of historic patterns of discrimination, Thompson wrote, “Denying felons the right to vote…runs against both the idea that people can redeem themselves and one of the nation’s most important principles, the right to choose who governs you.” Thompson quoted neoconservative social theorist James Q. Wilson: “A perpetual loss of the right to vote serves no practical or philosophical purpose.”19

Bob Wing, former editor of ColorLines magazine, described how even people of color who can vote are marginalized due to the two-party political system in the US. To win elections, both parties must take their most loyal voters for granted and focus their messages and money on winning over so-called undecided voters. The undecideds are mostly white, affluent suburbanites; both parties try to position their politics, rhetoric and policies to woo them. The interests of people of color are ignored or even attacked by both parties as they pander to a white center.20

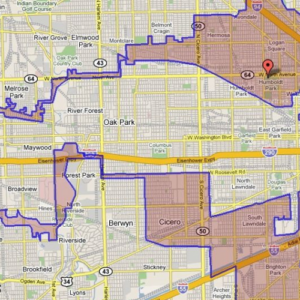

Illinois’ 4th Congressional District map shows one of the country’s worst cases of gerrymandering. (Image: SBTL1 / flickr Public Domain)

There are, of course, other strategies white people use to keep people of color from voting or to keep their votes from counting: at-large elections, gerrymandering,21) failure to redistrict when called for, packing (drawing electoral districts so the majority of a group is packed into one area, which therefore gives it only a single representative), and its opposite cracking (spreading out voters of color over several districts so their votes are diluted).j

Between 2010 and 2019, a total of 15 states have more restrictive voter ID laws in place (and six states have strict photo ID requirements), seven have laws making it harder for citizens to register, six cut back on early voting days and hours, and three made it harder to restore voting rights for people with past criminal convictions.22 Voters in the 2016 US presidential election faced long lines (at least 10 states reported waits of over an hour), malfunctioning voting machines (at least 13 states), confusion over voting restrictions (14 states), arbitrary and illegal removal of names from the voter rolls, and voter intimidation in several states.23

Finally, because the Electoral College vote distribution is tied to the census and we know the census undercounts communities of color, those communities lose political representation. The Census Bureau has refused to adjust the 2010 census results to account for a known undercount that leaves out at least 1.5 million people, all of whom are poor and many of whom are people of color. These data errors also have serious repercussions in the distribution of federal and state funds for social programs and community development grants.24

There is also evidence of serious electronic corruption in the voting system. Election fraud, election manipulation or vote rigging, is illegal interference with the process of an election, either by increasing the vote share of the favored candidate, depressing the vote share of the rival candidates, or both. “Online voting is such a dangerous idea that computer scientists and security experts are nearly unanimous in opposition to it,” states Stanford Engineering writer Ian Chipman. (Ian Chipman, “David Dill: Why Online Voting is a Danger to Democracy” Stanford Engineering, June 3, 2016) https://engineering.stanford.edu/magazine/article/david-dill-why-online-voting-danger-democracy ))

Image by Ranjithsiji is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Even without shifting online, the US voting system has proven insecure and riddled with conflicts of interest. Two manufacturers provide 80% of election equipment [PDF]25. Election Systems and Software, LLC (ES&S) along with Dominion Voting have a monopoly on how you cast your vote. They are both owned by private equity, or equity that is not publicly listed and traded. In other words, the public doesn’t know who funds and controls the very machines that they vote on.26

ES&S accounts for 44% of US election equipment27. The company got its start thanks to financing from the families of Nelson Bunker Hunt and Howard Ahmanson, Jr.–both right-wing billionaires28. These families have another financing interest: Christian reconstruction. They both gave major contributions to the Chalcedon Foundation, “a Christian education organization devoted to the research, publishing, and promotion of Christian Reconstruction.”29

Hunt and Ahmanson have more than just wealth and voting machines in common. They were both central early members of the Council for National Policy, a Religious Right organization that has networked figures like Kelly Anne Conway, Steve Bannon, Mike Pence, Richard DeVos, NRA’s Wayne LaPierre, Robert and Rebekka Mercer, and Bob Dallas. (Bob Dallas has been convicted of embezzling and his nonprofits have been connected to voter data leaks.)30

A corrupt Global/Diebold (now under ES&S) voting machine probably cost Gore as many as 16,000 Florida votes in his bid for president in the 2000 election. George W. Bush defeated him in Florida by 537 votes.31

Another company, Dominion, produces 37% of US election equipment and could very well have connections to ES&S. We know for sure that Dominion’s programming has ties to people who have been involved in Russian elections. The public doesn’t have access to who Dominion is connected to, however, because it is also owned by private equity.32

In recent elections we’ve seen the problems with vote-flipping, touch screen voting machines in Mississippi, Georgia, and Texas. And it has been confirmed that in some states such as Tennessee and Georgia voting machines seem to have been “losing” large numbers of votes from predominantly Black neighborhoods.33 Without a paper trail there is virtually no way to detect this kind of massive voter fraud. The situation will be no better if voters notice vote flipping or deletions on the paper printouts marked by a new generation of electronic ballot marking devices (BMDs). They only print a paper trail after any ballot tampering has been completed therefore they are no substitute for paper ballots.

The new systems are, by design, remarkably insecure—vulnerable to hacking (manipulation) at various stages of the voter verification, vote casting and tallying process. We saw in the 2016 election just how vulnerable they are when the Russians were able to hack voter registration databases.34 We probably have much more to fear from corporate and political ruling class manipulation of the vote than from the Russians because it is U.S. corporations and billionaires who create, own and adjudicate the entire system. There are approximately 350,000 voting machines in use in the country today, all of which fall into one of two categories: optical-scan machines or direct-recording electronic machines. Each of them suffers from significant security problems because of poorly designed machinery; from websites and databases that register and track voters; to electronic poll books that verify their eligibility; to the various black-box systems that tally, record and report results.

Photo by Tiffany Tertipes on Unsplash

On April 6, 2020, despite an Executive Order from the governor to extend absentee voting before the next day’s primary, the U.S. Supreme Court halted Wisconsin’s plan, resulting in thousands of late absentee ballots being thrown away.35 Voters in the state who requested absentee ballots weeks or even months ago didn’t receive their ballots until after the election due to disruptions caused by the coronavirus. Now they’ve been disenfranchised — not because they did anything wrong, but because the United States Supreme Court wanted to help out their Republican friends in Wisconsin by making it even more difficult for progressives and people of color to vote.

As Greg Palast has written recently “I get it. We must all vote by mail–or we die.”36 He immediately goes on to write “But there is much to fear, especially for minority and young voters, with a switch to all-mail voting–unless our broken absentee ballot system is fixed.” He then lists many ways voting by mail allows election officials to disenfranchise people of color and young voters. Some of the things he notes37:

- In 2016, 512,696 mail-in ballots —over half a million– were simply rejected, not counted.

- One study puts the total loss of mail-in votes at a breathtaking 22%. Move to 80% mail-in voting and 25 million will lose their vote. Overwhelming, those junked are ballots mailed by poorer, younger, non-white Americans.

- Vote by mail is not simple. Millions of low-income voters who rarely vote absentee will now have to fill out multi-step forms for the first time.

- Eight states, including the swing states of Wisconsin, North Carolina and Klobuchar’s Minnesota, require a mail-in voter to have the ballot signed by a witness.

- Three states, including swing state Missouri, require the ballot to be notarized.

- All but six states “verify” the voter’s signature against the voter’s registration signature.

- A national survey shows rejection rates for absentee votes were higher for Democrats than Republicans, higher for younger than older voters, and higher for non-English ballots.

- Some states require all or first-time voters to mail in a copy of their ID: another hurdle for the poor, those without driver’s licenses or those who may have the wrong ID and not know it. For example, college student IDs are not acceptable.

- 100,000 ballots are lost in presidential elections because of postage due.

- 4% to 20% of any mailing goes astray — leaving voting rights at risk for more than a million citizens simply from wrong and changed addresses.

- Another racist tactic was used by the Ohio electoral admin in 2016: they refused to send absentee ballot application cards to 1,0335,795 voters. An investigation found the purge list of “movers” (people who had allegedly moved) to be 70%+ wrong. Democrats were scrubbed at nearly twice the rate as Republicans.

- The US has a huge problem with “residual” votes when the voter’s choice is not readable by our counting machinery. African-Americans are five times as likely to have their vote disqualified for “over-voting” (making an extra mark on the ballot) than white voters.

- Several states use other methods to disqualify absentee ballots. Writing about his state’s record, attorney Prof. Robert Fitrakis of Columbus State University, says, “We have a history in Ohio of deliberately using the absentee ballot in a partisan and racist way.” For example, disqualifying mail-ins with such excuses as, “signature below line,” i.e. part of the signature was not perfectly inside a box.

As Palast concludes, “Nationwide, in the past two years (2018 and 2019), 17 million voters were erased from the voter rolls in a wave of Republican-led voter disenfranchisement. Given the massive errors resulting from this effort, millions of citizens, come November, will not find their expected ballot in their mailbox…Unless America radically changes the way we send, receive and count mail-in ballots, the massive switch to postal voting, and the mountain of uncounted minority votes it will generate, could lead to Trump’s re-election.” And, I would add, this will lead to the continuing massive voter disenfranchisement of people of color and other voters.

The ballot box is the foundation of any democracy. It’s not overstated to say that if there’s a failure in the ballot box, then democracy fails. If the people don’t have confidence in the outcome of an election, then it becomes difficult for them to accept the policies and actions that pour forth from it. And in the United States, it’s safe to say, though few may utter it publicly, that the ballot box has failed many times and is poised to fail again.38

Image by Truthout.org is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

White people often complain people of color don’t vote in large enough numbers. I’ve heard it said, “They must not care enough.” But how many white people would vote if they were harassed on the way to the poll and, after they traveled over an hour to get there and then waited a couple of hours in line, they were told they weren’t listed or they needed to show extra identification or the voting machines were broken? How many would vote if, when they tried to make a complaint, there was no one who spoke their language to help them, and all the complaint lines were busy and understaffed? How many would vote if they discovered later that many of their votes were thrown out because of “irregularities” in the ballots and voting machines? What if election fraud, deception and manipulation had been going on for over 150 years?

There are numerous places to begin overhauling the US voting system:

- Eliminate the Electoral College system and rely on a popular vote to determine the president

- Develop a system of proportional representation for elections (a system already in place in many municipalities and counties; various forms are used throughout the world)

- Institute federal monitoring of elections

- Allow for district voting in local elections

- Develop a multi-party system of government

- Redistrict by population, supervised by widely representative bodies of citizens from each community

- Remove restrictions on people who are ex-felons or on parole voting rights and set up programs to help them register, as Canada does

- Install modern, easy-to-use, transparent voting machinery that produces a paper record; keep polls open 24 hours or more; declare voting day a national holiday

- Institute election-day registration

- Demand that election-security legislation prioritize hand marked paper ballots and robust manual audits (and ban barcode voting)

- Insist that the House of Representatives subpoena the vendors to testify under oath about ownership, past security lapses, and where and when they have installed remote access software and wireless modems. (The Brennan Center of Justice also has a proposed framework for vendor accountability here.)

- Radically transform the way we send, receive and count mail-in ballots.

There are already community groups working on many of these issues.39 By becoming active on this issue, you are strengthening democracy.

See the movie Slay the Dragon ((Slay the Dragon, directed by Christopher Durrance and Barak Goodman, (2019; New York, Magnolia Pictures, 2020.)) (trailer below) for powerful examples of what grassroots organizing can accomplish.

There are myriad organizations to plug into:

- Fair Fight

- Let America Vote

- Common Cause

- Working Families Party

- American Civil Liberties Union

- The Brennan Center

- Campaign Legal Center

- Fair Vote

- The Sentencing Project’s Felony Disenfranchisement Project

- Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights

- The Leadership Council on Civil and Human Rights’ Voting Rights Project

- National Popular Vote

- Black Votes Matter

- Advancement Project

Further resources:

Berman, Ari. Give Us the Vote: The Modern Struggle for Voting Rights in America. Macmillian, 2015.

Daley, David. Ratf**ked: Why Your Vote Doesn’t Count. Liveright, 2017.

Daley, David. Unrigged: How Americans Are Battling Back to Save Democracy. Liveright 2020.

Hasen, Richard L., Election Meltdown: Dirty Tricks, Distrust, and the Threat to American Democracy. Yale University Press, 2020.

Daniels, Gilda R., Uncounted: The Crisis of Voter Suppression in America. NYU Press, 2020.

Anderson, Carol. One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression Is Destroying Our Democracy. Bloomsbury, 2018.

Curriculum Resources For Young People:

Anderson, Carol and Tonya Bolden. One Person, No Vote: How Not All Voters are Treated Equally. Bloomsbury, 2019.

“Campaign to Commemorate 150th Anniversary of the 15th Amendment.” Zinn Education Project.

“Teaching People’s History in the Pandemic.” March 30, 2020. Zinn Education Project.

Wolfe-Rocca, Ursula. “Who Gets To Vote? Teaching About the Struggle For Voting Rights in the United States.” Teaching Unit with Three Lessons. Zinn Education Project.

Wolfe-Rocca, Ursula. “What Our Students Should Know About the Struggle for the Ballot–but Won’t Learn From Their Textbooks.” The Washington Post. April 6, 2020.

Please send comments, feedback, resources, and suggestions for distribution to paul@paulkivel.com. Further resources are available at www.paulkivel.com.

All articles may be quoted, adapted, or reprinted only for noncommercial purposes and with an attribution to Paul Kivel, www.paulkivel.com. Creative Commons Attribution – Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit here.

Notes:

- Ken Drexler, “15th Amendment to the US Constitution,” Research Guides, Library of Congress, 2019, cited April 22, 2020, https://guides.loc.gov/15th-amendment [↩]

- Ken Drexler, “19th Amendment to the US Constitution,” Research Guides, Library of Congress, 2019, cited April 22, 2020, https://guides.loc.gov/19th-amendment [↩]

- “Congress and The Voting Rights Act of 1965,” The Center for Legislative Archives, 2019, cited April 22, 2020, https://www.archives.gov/legislative/features/voting-rights-1965 [↩]

- John Henley, “White and Wealthy Voters Gave Victory to Donald Trump, Exit Polls Show,” Guardian, (November 9, 2016), cited December 19, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/09/white-voters-victory-donald-trump-exit-polls [↩]

- Quick Facts United States, United States Census, 2019, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219 [↩]

- David Brion Davis. “The Central Fact of American History,” American-Heritage 65, no 1, (Feb-March 2005) cited December 19, 2016, https://www.americanheritage.com/central-fact-american-history [↩]

- Lara and Dean Baker Merling, “In the Electoral College White Votes Matter More,” Center for Economic and Policy Research, (November 14, 2016) cited November 26, 2016, https://www.cepr.net/in-the-electoral-college-white-votes-matter-more/ [↩]

- Adam Liptak, “Smaller States Find Outsize Clout Growing in Senate,” New York Times, (March 11, 2013) cited December 19, 2016, http://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/interactive/2013/03/11/us/politics/democracy-tested.html?hp [↩]

- Steven Hill, “Why Progressives Lose: Affirmative Action for Conservatives,” Center for Voting and Democracy (June 2003) cited December 19, 2016, http://archive.fairvote.org/articles/progressivepopulis.htm [↩]

- Quoted in Harmon v Forsennius 380 U.S. 528 (1965) cited April 12, 2017. [↩]

- Laura Conaway and James Ridgeway, “Democracy in Chains,” Village Voice, (November 28, 2000) cited (December 19, 2016) https://www.villagevoice.com/2000/11/28/democracy-in-chains/; Speech of Hon. John B. Knox of Calhoun County, President of the Late Constitutional Convention of Alabama, in Closing the Campaign in Favor of Ratification”(speech, Centerville, Alabama, November 9th, 1901) Alabama Department of Archives and History, cited April 20, 2020, https://digital.archives.alabama.gov/digital/collection/voices/id/8516 [↩]

- It is important to note that states where people of color are disenfranchised or where they receive the lowest wages are often the same states in which poor and working-class whites are disenfranchised and paid the lowest wages as well. [↩]

- The information following is adapted from: Manning Marable, “Stealing the Election: The Compromises of 1876 and 2000,” Standards 7, no. 2 (Spring-Summer 2001) cited December 19, 2016, https://web.archive.org/web/20171215184538/colorado.edu/journals/standards/V7N2/FIRST/marable.html [↩]

- “This Day in History: November 1, 1890: Mississippi Constitution.” Zinn Education Project, cited May 8, 2020, https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/mississippi-constitution/ [↩]

- Erika L. Wood, “Florida: An Outlier in Denying Voting Rights,” Brennan Center for Justice at NYU (2016) https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/publications/Florida_Voting_Rights_Outlier.pdf [↩]

- A common provision introduced in the South after the reconstruction period: only those whose grandfathers could vote could themselves vote, eliminating almost all blacks from voting rolls. [↩]

- Chris Uggen, Sarah Shannon and Arleth Pulido-Nava, “Locked Out 2020: Estimates Of People Denied Voting Rights Due to a Felony Conviction” Sentencing Project (October 30, 2020) https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/locked-out-2020-estimates-of-people-denied-voting-rights-due-to-a-felony-conviction/ [↩]

- Katie Rose Quandt, “1 in 13 African-American Adults Prohibited from Voting in the United States,” Moyers & Company (March 24, 2015) cited November 20, 2016, https://billmoyers.com/2015/03/24/felon-disenfranchisement/ Although rules vary state by state, the United States is the only industrialized country that denies former prisoners, who have completed their sentences and are fully integrated into the community, the vote. [↩]

- Nicholas Thompson,”Locking Up the Vote,” Washington Monthly (January 2001) cited December 19, 2016, https://washingtonmonthly.com/2001/01/01/locking-up-the-vote/ [↩]

- Bob Wing, “White Power in Election 2000,” ColorLines (March 15, 2001) cited December 19, 2016, https://www.colorlines.com/articles/white-power-election-2000 [↩]

- Bill Moyers, “Republicans Admit They Lose When Elections Are Fair and Free,” Common Dreams (April 10, 2020 [↩]

- Brennan Center for Justice, “New Voting Restrictions in Place for 2016 Presidential Election,” (Updated September 12, 2016) cited November 20, 2016. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/new-voting-restrictions-america [↩]

- Brennan Center for Justice, “Voting Problems Present in 2016, but Further Study Needed to Determine Impact,” Brennan Center for Justice, (November 15, 2016) cited November 20, 2016, https://truthout.org/articles/voting-problems-present-in-2016-but-further-study-needed-to-determine-impact/ [↩]

- David A. Love, “2010 Census Undercount Could Spell Disaster for Blacks, Latinos,” TheGrio (May 24, 2012) cited April 12, 2017, https://thegrio.com/2012/05/24/2010-census-undercount-could-spell-disaster-for-blacks-latinos/ [↩]

- The Business of Voting: Market Structure and Innovation in the Election Technology Industry. [PDF] University of Pennsylvania, 2017. [↩]

- The section draws extensively on research and reporting by Jennifer Cohn, “Americans Electronic Voting System is Corrupted to the Core,.” Medium (September 7, 2019) cited March 31, 2020, https://jennycohn1.medium.com/americas-electronic-voting-system-is-corrupted-to-the-core-1f55f34f346e [↩]

- The Business of Voting [↩]

- John Snugg, “A Nation Under God,” Mother Jones, (December 2005) https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2005/12/nation-under-god/ [↩]

- Cohn; “About,” Chalcedon Foundation, cited May 8, 2020, https://chalcedon.edu/about [↩]

- Heidi Beirich and Mark Potok, “The Council for National Policy: Behind the Curtain,” Southern Poverty Law Center, (May 17, 2016) cited May 8, 2020, https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2016/05/17/council-national-policy-behind-curtain ; “Howard F. Ahmanson, Jr.,” Nation Master Encyclopedia, cited May 8, 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/20191105105319/http://www.statemaster.com/encyclopedia/Howard-F.-Ahmanson,-Jr; Cohn [↩]

- Cohn; Bob Fitrakis and Harvey Wasserman, “Diebold’s Political Machine,” Mother Jones, (March 5, 2004) cited May 8, 2020, https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2004/03/diebolds-political-machine/ [↩]

- Cohn; Patrick Howell O’Neill, “16 Million Americans Will Vote on Hackable Paperless Machines,” MIT Technology Review, (August 13, 2019) cited May 8, 2020, https://www.technologyreview.com/2019/08/13/238715/16-million-americans-will-vote-on-hackable-paperless-voting-machines/ [↩]

- Read more on Diebold machine and the shady history connecting computerized voting, voting machines and the GOP in this Mother Jones article. [↩]

- Matthew Cole, Richard Esposito, et al, “NSA Report on Russian Hacking Effort Days Before 2016 Election,” The Intercept, (June 5, 2017) https://theintercept.com/2017/06/05/top-secret-nsa-report-details-russian-hacking-effort-days-before-2016-election/ [↩]

- The Republican National Committee v. The Democratic National Committee, 589 US Supreme Court (2020). [↩]

- Greg Palast, “Rush to Vote-by-mail could cost the Dems the Election,” Nation of Change, (April 16, 2020) cited on April 20, 2020, https://www.nationofchange.org/2020/04/16/exclusive-rush-to-vote-by-mail-could-cost-dems-the-election/ [↩]

- The following bulleted list is largely verbatim from Palast. [↩]

- Kim Zetter, “The Crisis of Election Security: As the midterms approach, America’s electronic voting systems are more vulnerable than ever. Why isn’t anyone trying to fix them?” New York Times Magazine, (Sept. 26, 2018) cited April 2, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/26/magazine/election-security-crisis-midterms.html [↩]

- For inspiring stories about how people are organizing to reclaim our democracy see David Daley’s Unrigged: How Americans Are Battling Back to Save Democracy, (New York: Liveright, 2020). [↩]