By Paul Kivel. Updated December 4, 2020. (Original article from 2000) ((©2000 Paul Kivel. My thanks to Bill Aal, Luz Guerra, Nell Myhand, and Suzanne Pharr for encouragement and suggestions about this article.))

Photo by Sandy Millar on Unsplash

Note: Since the pandemic inequality has increased dramatically, billions of dollars have flowed to the top 1% and millions more are now un- or under-employed. In a time when three white Christian men control more wealth than the bottom 50% of the population, the questions raised in this article are more urgent than ever.

MY FIRST ANSWER TO THE QUESTION “Social service or social change?” is that we need both, of course. We need to provide services for those most in need, for those trying to survive, for those barely making it. We need to work for social change so that we create a society in which our institutions and organizations are equitable and just and all people are safe, adequately fed, adequately housed, well educated, able to work at safe, decent jobs, and able to participate in the decisions that affect their lives.

Although the title of this article may be misleading in contrasting social service provision and social change work, the two do not necessarily go together easily and in many instances do not go together at all. There are some groups working for social change that are providing social service; there are many more groups providing social services that are not working for social change. In fact, many social service agencies may be intentionally or inadvertently working to maintain the status quo.

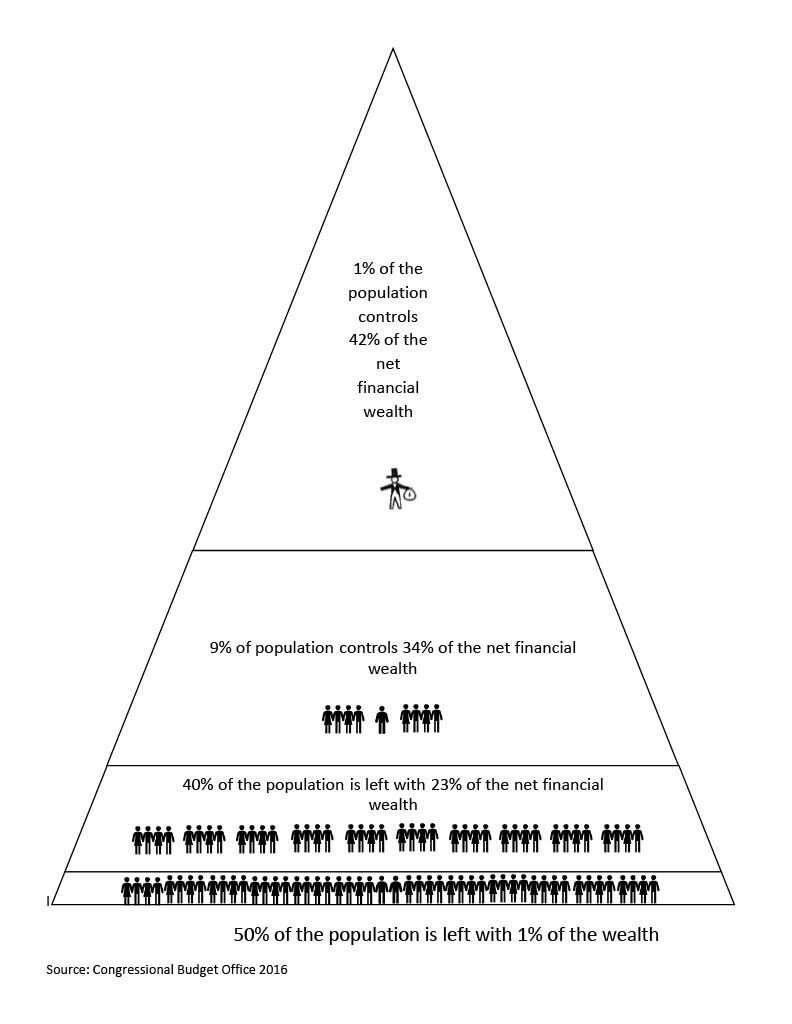

The Economic Pyramid

I want to begin by providing a context for this discussion: the present political/economic system here in the United States. Currently our economic structure looks like the pyramid in this PDF in which 1% of the population controls about 42% of the net financial wealth1 of the country, and the next 9% of the population controls another 34%. That leaves 90% of the population struggling to gain a share of just 24% of the remaining financial wealth. That majority of 90% doesn’t divide very easily into 24% of resources, which means that many of us spend most of our time trying to get enough money to feed, house, clothe, and otherwise support ourselves and our families.

There are many gradations in the economic pyramid. Among the 90% at the base of the pyramid there is a huge difference in the standard of living between those nearer the top in terms of average income and/or net worth, and those near or on the bottom. 50% of the population at the bottom divide 1% of the wealth. There is also a substantial number of people who are actually below the bottom of the pyramid with negative financial wealth, i.e. more debt than assets.

Regardless of these complexities, there is a clear and growing divide between those at the base and those in the top 20% who have substantial assets providing them with security, social and economic benefits, and access to power, resources, education, leisure, and health care. Most of the rest of the population have an increasingly limited ability to achieve these benefits if they have access to them at all.2

I will refer to the top 1% as the ruling class because members of this class sit in the positions of power in our society as corporate executives, politicians, policy makers, and funders for political campaigns, policy research, public policy debates and media campaigns. I call them a ruling class because they have the power and money to influence and often to determine the decisions that affect our lives, including where jobs will be located and what kind of jobs they will be, where toxics are dumped, how much money is allocated to build schools or prisons and where they will be built, which health care, reproductive rights, civil rights, and educational issues will be discussed and who defines the terms of these discussions. In other words, when we look at positions of power in the U.S. we will almost always see members or representatives of the ruling class.

The ruling class does not all sit down together in a room and decide policy. However, members of this class do go to school together, vacation together, live together, socialize together, and share ideas through various newspapers and magazines, conferences, think tanks, spokespeople, and research and advocacy groups. Perhaps most importantly, members of this class sit together on interlocking boards of directors of major corporations and wield great direct power on corporate decisions. They wield almost as great a power on political decisions through lobbying, government appointments, corporate funded research, interpersonal connections, and advisory appointments.3

Photo by Marvin Meyer on Unsplash

The next 9% of the economic pyramid are people who work for the ruling class, whose jobs don’t carry the same power and financial rewards, but whose purpose is to provide the research, skills, expertise, technological development and other resources which the ruling class needs to maintain and justify its monopolization of political and economic power.

The other 90% of the population produces the social wealth that those at the top benefit from. They work in the factories, fields, classrooms, homes, sweatshops, hospitals, restaurants, small businesses, behind the phones, behind the desks, behind the wheel, and behind the counter, doing the things that keep our society functioning and productive. They are caught up in cycles of competition, scarcity, violence, and insecurity that those at the top are largely protected from.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELF

• Where did you grow up on the pyramid, or where was your family of origin on the pyramid?

• Where are you now?

People at the bottom of the pyramid are constantly organizing to gain more power and access to resources. Most of the social change we have witnessed in U.S. history has come from people who are disenfranchised in this system fighting for access to education, jobs, health care, civil rights, reproductive rights, safety, housing, and a safe, clean environment. In our recent history we can point to the Civil Rights Movement, women’s liberation movements, lesbian and gay liberation movements, disability rights movement, unions, and thousands of local struggles for social change.4

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELF

• Are you part of any group which has organized to gain for itself more access to voting rights, jobs, housing, education, or an end to violence or exploitation such as workers, women, people of color, people with disabilities, seniors, youth, lesbians, gays, bisexuals and trans people, or people whose religion is not Christian?

• How have those struggles benefited your life?

• How have those struggles been resisted by the ruling class?

• What is the current state of those movements you have been closest to?

The Buffer Zone

People in the ruling class have always avoided dealing directly with people on the bottom of the pyramid and they have always wanted to keep people from the bottom of the pyramid from organizing for power so that they could maintain the power, control, and most importantly, wealth that they have accumulated. They have created a network of occupations, careers, and professions to mediate for and buffer them from the rest of the population. This buffer zone consists of all the jobs that carry out the agenda of the ruling class without requiring ruling class presence or visibility. Some of the people doing these jobs fall into the 19% section of the pyramid, often performing work that serves the ruling class directly. However, most of the people in the buffer zone have jobs that put them into the top of the bottom 90%. These jobs give them a little more economic security and just enough power to make decisions about other people’s lives—those who have even less than they do. The buffer zone has three primary functions.

The first function is to take care of people on the bottom of the pyramid. If it was a literal free-for-all for that 9% of social wealth allocated to the poor/working/and lower middle classes there would be chaos and many more people would be dying in the streets, instead of dying invisibly in homes, hospitals, prisons, rest homes, homeless shelters, etc. So there are many occupations to sort out which people get how much of the 9%, and to take care of those who aren’t really making it. Social welfare workers, nurses, teachers, counselors, case workers of various sorts, advocates for various groups—these occupations, which are found primarily in the bottom of the pyramid, are performed mostly by women, and are primarily identified as women’s work, taking care of people at the bottom of the pyramid.

The second function of jobs in the buffer zone is to keep hope alive. To keep alive the myth that anyone can make it in this society—that there is a level playing field. These jobs, often the same as the caretaking jobs, determine which people will be the lucky ones to receive jobs and job training, a college education, housing allotments, or health care. These people convince us that if we just work hard, follow the rules, and don’t challenge the social order or status quo, we too can get ahead and gain a few benefits from the system. Sometimes getting ahead in this context means getting a job in the buffer zone and becoming one of the people who hands out the benefits.

The final function of jobs in the buffer zone is to maintain the system by controlling those who want to make changes. Because people at the bottom keep fighting for change, people at the top need social mechanisms that keep people in their place in the family, in schools, in the neighborhood, and even overseas in other countries. Police, security guards, prison wardens, soldiers, deans and administrators, immigration officials, and fathers in their role as “the discipline in the family”—these are all traditionally male roles in the buffer zone designed to keep people in their place in the hierarchy.5

“Riot Control” by Steve Crane is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

During the last half of the 20th century when multiple groups were demanding—and in some cases getting—critical changes in our social structure such as better access to jobs, education, and health care, the ruling classes needed a new strategy to avoid an all out civil war. (Hear Paul Kivel use the example of the COVID-19 pandemic to illustrate how the buffer zone strategy can be used to manage unrest during crisis.)

Co-opting social change

This strategy has been to create professions drawn from the groups of people demanding change of the system, creating an atmosphere of “progress,” where hope is kindled, and needs for change are made legitimate, without producing the systematic change which would actually eliminate the injustice or inequality which caused the organizing in the first place. This process separates people in leadership from their communities by offering them jobs providing services to their communities and steering their interests towards the governmental and non- profit bureaucracies that employ them. This process has the effect of creating new groups of professionals providing social services without necessarily producing greater social justice or equality of opportunity.5

One example of how this process works can be seen in the Civil Rights Movement, which was a grassroots struggle led by African Americans for full civil rights, for access to power and resources, and for the end of racial discrimination and racist violence. Although legalized segregation was dismantled as a result of those struggles, the broader racial and economic goals of the movement have largely remained unfulfilled. However we now have a larger African American middle class because some opportunities opened up in the buffer zone: in the government, in middle management and academic jobs, and in the non-profit sector.

The issue of racism is now “addressed” in our social institutions by a multiracial group of professionals who work as diversity or multicultural trainers, consultants, advisors, and educators. Although the ruling class is still almost exclusively white and most African Americans, Native Americans, and other people of color remain at the bottom of the economic pyramid, there is the illusion that substantial change has occurred because we have a few very high profile wealthy people of color. Bill Cosby, Oprah Winfrey, Michael Jordan and others are held up as examples to prove that any person of color can become rich and powerful if they work at it.

The Civil Rights Movement is not the only arena where this process has occurred. Another example is the battered women’s movement, the organizing by battered and formerly battered women for shelter, safety, resources, and an end to male violence. Again, some gains were made in identifying the issue, in improving the response of public institutions to incidents of male violence, and in increasing services to battered women. But systematic, large-scale efforts to mobilize battered women and end male violence have not been attempted. Instead, we have a network of (still largely inadequate) social services to attend to the immediate needs of battered women, and a new network of buffer zone jobs in shelters and advocacy organizations to administer to those needs.

Photo by Piotr Makowski on Unsplash

In both of these examples we can see that the roots of racism and male violence are not being addressed. Instead we have new cadres of professionals who administer to the needs of those on the bottom of the pyramid. In fact, in both of these cases we now have more controlling elements—more police, security guards, immigration officials, etc. than ever before—whose role is to reinforce the racial hierarchy and reach into the family lives of poor and working class white people and people of color.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELF

• Who are you in solidarity with in the pyramid—who would you like to support through the work that you do—people at the top of the pyramid, people in the buffer zone, or people at the bottom?

• What are the historical roots of the work that you do?

• What were your motivations or intentions when you began doing this work?

• Who actually benefits from the work that you do?

• Are there ways through your work, your family role, or your role in the community that you have come to enforce the status quo or train young people for their role in it?

The Role of the Non-profit

A primary vehicle that the ruling class created to stabilize the buffer zone was the non-profit organization. The non-profit tax category was created to give substantial economic benefits to the ruling class while allowing them to fund services for themselves. Even today, most charitable, tax exempt giving from the ruling class goes to ruling class functions like museums, operas, art galleries, elite universities, private hospitals and family foundations. A second effect of the non -profit sector has been to provide a vehicle for the ruling class to fund (and therefore to control) work in the buffer zone. A large amount of the money donated to non-profits either comes from charitable foundations or from direct donations by members of the ruling class. Non-profits serving the 90% at the pyramid’s base often spend inordinate amounts of time writing proposals, designing programs to meet foundation guidelines, tracking and evaluating programs to satisfy foundations, or soliciting private donations through direct mail appeals, house parties, benefits, and other fundraising techniques. Much of the work of many non-profits is either developed or presented in such a way as to meet the guidelines and approval of people in or representing the ruling class. Within the last twenty years, due to the massive cutbacks in government support services and thus the greater dependence of non-profits on non-governmental funding, this process has been exacerbated.

The ruling class established non-profits to provide social services. Jobs were professionalized historically to co-opt social change. Funders today generally look for non-profit programming that fills gaps in the provision of services, extends outreach to underserved groups, and stresses collaborations which bring together several services providers to use money and other resources more efficiently. It should not be surprising that so much of the work of the buffer zone is social service—keeping hope alive by helping some people get ahead.

How does co-optation work?

The ruling class co-opts the leadership in our communities by providing jobs for some people and aligning their perceived self interest with maintaining the system (maintaining their jobs). Whether they are social welfare workers, police, domestic violence shelter workers, diversity consultants, therapists, or security guards, their jobs and status are dependent on their ability to keep the system functioning and to keep people functioning within the system no matter how illogical, dysfunctional, exploitive, and unjust the system is. The very existence of these jobs serves to convince people that tremendous inequalities of wealth are natural and inevitable and those that work hard will get ahead. As the following quote makes clear, integrating the leadership of our communities into the bureaucracies of the buffer zone separates the interests of those leaders from the needs of the community.

Co-optation is a process through which the policy orientations of leaders are influenced and their organizational activities channeled. It blends the leader’s interests with those of an external organization. In the process, ethnic leaders and their organizations become active in the state-run inter-organizational system; they become participants in the decision-making process as advisors or committee members. By becoming somewhat of an insider the co-opted leader is likely to identify with the organization and its objectives. The leader’s point of view is shaped through the personal ties formed with authorities and functionaries of the external organization.6

Ruling class policies, including development of the non-profit sector and support for social services, have led to the cooptation of substantial numbers of well-intentioned people. In this group I include all of us whose heart work—whose intention—is to help people at the bottom of the pyramid, but who’s work, in practice, substantially benefits people at the top of the pyramid and leaves the system unchanged.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELF

• Do you work in a non-profit organization?

• Where does the funding come from for your work?

• In what ways does the funding influence how the work gets defined?

• How much time do you spend responding to the needs of funders as opposed to the needs of the people you serve?

• In what ways has the staff of your program become separated from the people they serve because of

a. the demands of funders?

b. the status and pay of staff?

c. the professionalization of the work?

d. the role of your organization in the community?

e. the interdependence of your work with governmental agencies, businesses, foundations, or other nonprofit organizations?

• In what ways have your ties with governmental and community agencies separated you from the people you serve?

• In what ways have those ties limited your ability to be “contentious”—to challenge the powers that be and their undemocratic and abusive practices?

Getting Ahead or Getting Together

Image by Budzlife and is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Getting ahead is the mantra of capitalism. Getting ahead is what we try to do in our lives. Getting ahead is what we urge our children to do. Getting ahead is how many of us define success. The United States is built on the myth that the deserving get ahead. Many people believe that it is the responsibility of our society to see to it that everyone has an equal opportunity to get ahead. Many of our recent political struggles around civil rights, affirmative action, and the end of various forms of discrimination against lesbians, gay, bisexuals, trans people, people with disabilities, women, people of color, and recent immigrants have become defined as struggles for equal opportunity for everyone to compete to get ahead.

But in a pyramid shaped economic system only a few can get ahead. Many are doomed to stay exactly where they are at the bottom of the pyramid, or even to fall behind. With so much wealth concentrated in the top of the pyramid there are not enough jobs, not enough housing, not enough health care, not enough money for education for most people to get ahead.

How does the system change? How do people gain access to money, jobs, education, housing, and other resources? Historically, change happens when people get together. In fact, we have a long history—thousands of examples—of people getting together for social change, some of which I mentioned earlier in the article. Each of these efforts involved people identifying common goals, figuring out how to work together and support each other, and coming up with strategies for forcing organizational and institutional change. When people get together they build community by establishing projects, organizations, friendships, connections, coalitions, alliances, and understanding of differences. They do not acquiesce to, but rather fight against the agenda of the ruling class. They are in a contentious relationship to power.7)

When we provide social services to help people get ahead we can also help them get together with others for social empowerment. People are dying and they need help. Providing services gives us contact with community members, gives us credibility and experience upon which we can build strategies for social change. I think the difference between getting ahead individually and getting together as a group can guide us in thinking about whether we are empowering people to work for social change at the same time as we are providing them with social services.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELF

• Is the primary goal of the work you do to help people get ahead or to help them get together?

• How do you connect people to others in their situation?

• How do you nurture and develop leadership skills in the people you serve?

• How do you insure that they represent themselves in the agency and other levels of decision making that affect their lives?

• Do you provide them with information not only related to their own needs, but about how the larger social/ political/ economic system works to their disadvantage?

• Do you create situations in which they can experience their personal power, their connection to others, and their ability to work together for change?

• Do you help people understand and feel connected to the ongoing history of people’s struggles to challenge violence, exploitation, and injustice?

Looking at Domestic Violence

Let’s look at domestic violence work as an example. If we see battered women as victims we will naturally try to protect them from further violence, provide them with services, and try to help them “get ahead.” We will treat them individually, as clients, and hold the people (primarily men) who beat them accountable for their violence through stronger criminal justice sanctions and batterer’s groups. We would try to help battered women get out of battering relationships and to move forward in their lives. We would be advocates for more services, better services, culturally competent services, multilingual services, and we would advocate for strong and effective sanctions against men who are batterers. We would measure our success by how many battered women we served, and our success stories would be about how individual women were able to escape the violence of abusive families and get on with their lives. Our advocacy success stories would be about how various communities of women were provided better services and how batterers were met with more effective responses.

Photo by Maxim Hopman on Unsplash

However, we could understand that battered women are caught in cycles that are the result of the systematic exploitation, disempowerment, and isolation of women in our society, kept in battering relationships by community tolerance for male violence, lack of well-paying jobs, lack of decent childcare and affordable housing, and most of all by their isolation from each other and from the information and resources they need to come together to effect change.

If this were our analysis of domestic violence, then our primary strategies would involve providing battered women and their allies with the information, resources, connection, and organizing strategies they need to come together for substantial social change. We would be providing organizational and structural support for battered women to come together to act on their own behalf. We would not be working for battered women, we would be working with them. They would be us—battered women would be in leadership and hold the jobs that currently many non-battered women do. We would be organizers and resource providers, looking to battered women for leadership in the movement to end male violence. We would measure success by the strength of our programs for leadership development, community response to domestic violence, changes in the educational, housing, job, criminal justice, and social service institutions which condone or encourage male violence and which keep women trapped in abusive relationships. Our success stories would be about how battered women became leaders, educators, and organizers and how communities of people came together to understand male violence, develop strategies, and wield power.

The buffer zone strategy of the ruling class works very smoothly, so smoothly that many of us don’t notice that we are encouraged to feel good about helping a small number of individuals get ahead, while large numbers of people remain exploited, abused, and disenfranchised. Some of us have stopped imagining that we can end domestic violence and have, instead, built ourselves niches in the edifice of social services for battered women or for batterers.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELF IF YOU WORK IN A DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AGENCY

• Can you imagine an end to domestic violence?

• What do you think it will take?

• Does the work that you do contribute to ending domestic violence? How?

• How are battered women seen in your agency?

• Are you providing social service and/or are you working for social change?

• Are you helping battered women see that they are not alone, their problems not unique, their struggles interrelated?

• Are you helping them come together for increased consciousness, resource sharing, and empowerment?

What We Do Matters

“Even if it is not possible to change the system from within, an individual’s actions within the system do matter. We can accept or reject, promote or hinder the state’s agenda.”8

Without accountability to grassroots community struggles led by people at the bottom of the pyramid it becomes very easy to acquiesce to the ruling class’s agenda.

No one in the United States lives outside the pyramid. We all have jobs that have been set up to funnel benefits up the pyramid and to maintain the status quo. Those of us who are among the bottom 90% and who want to work for social change must do that work subversively. We must make strategic decisions about what the fundamental contradictions are in the system and how we can work together with others to expose those contradictions. We must use our resources, knowledge, and status as social service providers to educate, agitate, and organize for social change. We must refuse to be used as buffer zone agents against our communities. Instead we can come together in unions, coalitions, organizing projects, alliances, networks, support and advocacy groups and a multitude of other forms of action against the status quo.

I am convinced that if we are just trying to get ahead ourselves, or are altruistically trying to help others get ahead, we will remain part of the problem, part of the economic, political, and social structure that maintains the ruling class in power. It is only when we get together with others, and see our work as that of helping people come together for power that our social service work will lead to social change.

Photo by Ryoji Iwata on Unsplash

Accountability

“So the question is, how do we maintain a critical transformative edge to our politics when we are building that politics in an organizational environment that is shaped by institutions outside of our community that don’t necessarily want to see us survive on the terms that we are defining for ourselves?”9

How do I know if I am being co-opted and just providing social service, or if I am truly helping people get together? I cannot know by myself. I cannot know just from some people telling me that I am doing a good job, or telling me that I am making a difference. I cannot know by whether I feel good about what I do. Popularity, status, good feelings, positive feedback—these are all provided by our society to a range of people many of whom are not working for social good at all, much less for social change. I would like to look at the question of accountability because if I am in the buffer by job function or economic position the key question I have to confront is “Who am I accountable to?”

Since my work occurs in an extremely polarized and unequal economic hierarchy, and in an increasingly segregated and racially polarized society, I can begin to answer this question by analyzing the effects of my work on communities at the bottom of the pyramid to see if it contributes to perpetuating inequality or to promoting social justice.

It is easy for me to forget that I am only able to work inside non-profits, schools, and other social service organizations because so many people organized from the outside as part of the Civil Rights Movement, the women’s movement, the lesbian, gay, bisexual liberation movement, and disability rights movement. As I have become professionalized, dependent on this work for my livelihood, and caught up in the exigencies of doing the work, there has been a strong tendency for me to become more and more disconnected from the everyday political struggles in my community for equal opportunity, access to training and jobs, comparable pay and an end to sexual and racial harassment and violence—those social justice issues from which my work originally grew.

Even from within large organizations and institutional structures it is possible to work for social justice. It is possible to serve the interests of the poor and working class, people of color and women, lesbians, gays and bisexuals and people with disabilities more effectively. But doing so is not without risk.

We each need to determine the amount we can personally risk financially against the spiritual, emotional and community risks we bear by not standing by our commitment to social justice. These are strategic decisions that I don’t think one can make in isolation from the inside of the organization(s) we work for. Our work is part of a much wider network of individuals and organizations working for justice on the outside. To make effective decisions about our own work we need to be accountable to those groups and their actions and issues. This accountability then becomes a source of connection that breaks down isolation and increases our effectiveness as social justice activists.

I’d like to end this article with some suggestions for thinking about accountability in this context. I want to focus on racism as an example as I look at six questions I think we need to ask ourselves in the current political context.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELF

Who supervises your work?

I don’t mean who employs you or hires or funds you, although that is an important consideration in a conservative political climate when jobs are scarce. Who are the grassroots activists who advise you, who review your work, and with whom you consult? If you are male it is particularly important that you be accountable to women who are working to end male violence. If you are white it is critical for you to be accountable to people of color so that your work doesn’t inadvertently fuel the backlash or otherwise make it more dangerous for people of color. If you are a person with economic privilege you need to be listening to the voices of poor and working class people. This is about politics, not identity. Regardless of your ethnicity, race, or economic position, you need to be accountable to people who are on the front lines—who are organizing for social justice and an end to male violence. I think this has to be a dialectical process because there are people of color, feminists, working class activists who say conflicting things about what we should be doing and even about what the issues are. Some are even spokespeople for the ruling class. You have to be engaged in a critical dialogue, while recognizing that you have been trained to have the answers and not to listen to those who have less social and political power than you do. Therefore you have to consult thoroughly and extensively within the larger community.

Are you involved in community-based anti-violence struggle?

If you are not actively involved in the struggle for affirmative action, for immigrant rights, against environmental dumping, against police brutality, for access to health care, or against male violence, how are you learning? What are you modeling? What practice informs your work? Can you be accountable to communities struggling to end male violence if you are not politically involved yourself in some aspect of that struggle?

Are current political struggles part of the content of what you do?

Photo by Clay Banks on Unsplash

Do you connect the participants in your programs/ services/ trainings to opportunities for on-going political involvement? Do you work with participants on issues they define, or on issues you or funders or other’s in the buffer/power zone define? Do you give participants tools and resources for getting involved in the issues they identify as most immediate for them, whether those are public policy issues such as immigration, affirmative action, welfare, or health care, or workplace, neighborhood, and community issues such as jobs, education, violence, and toxic waste? When they leave the room after contact with you can they connect what they just learned to the violence they experience in their lives? Are you responsive to their needs for survival, safety, economic well-being, and political action?

Are you in a contentious relationship to those in power?

The ruling class—those at the top of the pyramid—have an aggressive and persistent agenda to disempower and exploit those at the bottom. If you are accountable to those at the bottom of the pyramid, you will necessarily be challenging that agenda. Are you willing to speak truth to power even at the risk of your job or of future employment by certain agencies? Do you ever hold back your real opinion so as not to make waves when you are at the “power-sharing” table? How have you come to justify your reluctance to challenge power?

Are you sharing power and access to power and resources with those on the frontlines of the struggle?

Do you systematically connect people in grassroots efforts to information, resources, supplies, money, research, and to each other? Are you willing to do this without getting to be a part of the resulting group efforts?

Do you help people come together?

Being accountable implies a cohesive or coherent community to be accountable to. Few such communities exist in our society and even fewer of us are connected to them. I believe that being accountable means nurturing and supporting the growth and stability of cohesive communities. Whether you are working with battered women, students, recent immigrants, or any other group, they are part of a community whether or not they perceive themselves to be. Are you strengthening that community, helping support the bonds between people? Do the battered women who leave your program understand themselves in connection/ relationship to other battered women and their allies? Do the students in your classroom see themselves as part of a community of learners and activists? Social change grows out of people understanding themselves to be interdependent, sharing common needs, goals, and interests. Are you helping people see they are not alone, their problems not unique, their struggles interrelated? Are you helping them come together for increased consciousness, resource sharing, and empowerment?

Who we are accountable to is a crucial concern in a contracting economy during conservative political times in which racial, sexual, and homophobic backlash is widespread. You may be discouraged about the possibility of doing effective political work in this context. You may be fearful of losing your jobs and livelihoods or lowering your standard of living. These are real concerns. But this is also a time of increasing and extensive organizing for social justice. It is an opportunity for many of us to realign ourselves clearly with those organizing efforts and reclaim the original vision of social justice, equality, and an end to the violence and exploitation which brought us into this work.

Please send comments, feedback, resources, and suggestions for distribution to paul@paulkivel.com. Further resources are available at www.paulkivel.com.

All articles may be quoted, adapted, or reprinted only for noncommercial purposes and with an attribution to Paul Kivel, www.paulkivel.com. Creative Commons Attribution – Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit here.

Endnotes

- Net financial wealth refers to all the wealth that a person owns excluding housing, minus their debts. It would include banking and savings accounts, stocks and bonds, commercial land and buildings, etc. [↩]

- Numbers based on 2016 data from the Congressional Budget Office. [↩]

- A full analysis of how the ruling class and power elite control power and wealth, can be found in my book You Call This a Democracy? Who Benefits, Who Pays, and Who Decides, (Lanham, MD: Apex Press, 2004). Note that this book is now distributed by Rowman & Littlefield. [↩]

- See Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, (New York: HarperCollins, 2015) for a history of these struggles by groups in the bottom of the pyramid. [↩]

- These distinctions in function are not always so separate in practice. For instance many taking care of roles such as social worker also have a strong client control element to them, and the police are now trying to soften their image by resorting to community policing strategies to build trust in the community. [↩] [↩]

- R. Breton, The Governance of Ethnic Communities: Political Structures and Processes in Canada quoted in Taiaiake Alfred, Peace, Power, Righteousness: an indigenous manifesto, (Ontario: Oxford University Press Canada, 2000), p.74. [↩]

- I am indebted to Taiaiake Alfred in his book Peace, Power, Righteousness: an indigenous manifesto for this terminology. (See page 76. [↩]

- Taiaiake Alfred, Peace, Power, Righteousness, 76. [↩]

- Tamara Jones. “Building Effective Black Feminist Organizations,” Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Society 2, No. 4 (Fall 2000): 55. [↩]